Maradona is dead. History will record he died Wednesday Nov 25th 2020 of a heart attack at the age of 60.

That I don’t have to tell you which Maradona. That I only have to use his surname. This tells you everything about the global reach of a hard-scrabble youngster who became a footballing icon for Argentina and some of the biggest clubs in Europe.

Maradona, whose greatest moment - and most villainous in the eyes of all of England - was his disputed goal in the World Cup finals of 1986.

It was either a travesty of justice that the referee failed to see how a five-foot-five player could out-jump towering English goalkeeper, Peter Shilton, and head the ball into the net, without handling the ball. Or it was the greatest con-trick by a struggling nation still smarting over the loss of the Falklands War to the old empire.

Either way, Maradona called it the “hand of God” goal. But credit where credit is due, he followed it up on the pitch four minutes later, with a goal of such brilliance that the great English striker Gary Lineker, also on the pitch, found himself applauding.

Those two moments summed up his career. Sublime on one hand. Troubled and troublesome on the other. A man revered on football’s biggest stages. A man reviled for his association with Mafia thugs and Fidel Castro. Huge contradictions.

A man generous to a tee with the poor of his local neighbourhoods. A man awash in bling and with a cocaine bill that would have paid the electricity costs of a small town for a year.

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn was right when he said that the fault line between good and evil runs through every human heart. Maradona, as all of us are, was a series of contradictions. His were just played out on a bigger stage.

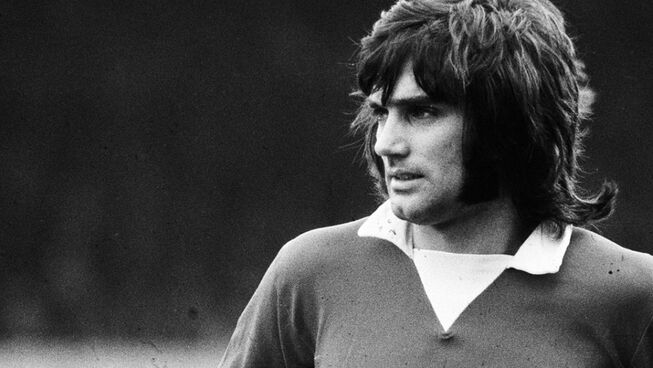

Maradona died fifteen years to the day of another football legend, Northern Ireland and Manchester United star, George Best. Best was also a man of contradictions.

For Best the fault line between good and evil ran through another organ altogether, his liver. Despite having a transplant due to his drinking, he continued his lifestyle and died of complications related to autoimmune suppressants.

Best wasn’t quite global enough to be known only by his surname alone, but when people say “Pele, Maradona and Best”, everyone who loves football gets it. It’s a holy Trinity.

Maradona would have disagreed.

Unlike the Persons of the Trinity, the Argentinian was never keen to share fame, or give glory to the other two, the very essence of the Bible’s teaching about God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. He stormed out of a FIFA presentation when Pele was named player of the century. Here's what he said:

My mother believes I am the best. And most people believe my mother.

Well, was the best. Was. Past tense. It’s astonishing how little time is afforded athletes to shine in their pomp. Just four years later Argentina lost the final to Germany in 1990, and then in USA 1994, he was kicked out in disgrace after failing a drugs test.

Sport eclipses us quicker than anything else. 26 years of age to reach the pinnacle with that goal, then a mere 34 years later, a decline that ends in a premature death.

Best too. He didn’t make 60. Died at 59. 361 appearances for the great Manchester United up until the age of 28, before being reduced to a circus oddity, travelling the world for appearance money. A half season here, a handful of games there, all for no-name clubs.

In 1982, When I was 14, he visited my high school in Northern Ireland. The lunch ladies swooned and shrieked and we all yelled and ran to the windows.

He played that night as a guest for local club Portadown FC. I went to watch in the tepid Ulster rain with thousands of others. We saw a touch or two of razzle-dazzle and roared like we thought it might sound at Old Trafford. But they were just touches - a memory of what had been. He was only 38.

Football is a game of two halves. But so is life. And both Maradona and Best played a poorer second half. Sports stars often do. And not just because of sport. Because of life. Because they are ill-prepared for what it means psychologically, emotionally and spiritually to have peaked early.

When the second half of life seems like it has nothing to offer compared to the first half, then you’re in trouble. Truly great sportspeople have amazing first halves of life. Truly great people who are truly great at sport seem to loose the surly bonds of retirement and many have amazing second halves of life.

Think Johan Cruyff - the man who masterminded for the Dutch what we call “total football”, and who then became a brilliant manager upon retirement.

And a brilliant father. His son Jordi - also a great player - once said that football was only ever a means to an end for his late father. And that end was to help and encourage as many people who needed it as he could. What a second half legacy!

Two other great footballers - not household names - but names to those who know football well, have also played that second half much better.

And much of that has to do with where they find their true source of worth. Gavin Peacock, the Newcastle United and Chelsea FC star, turned to Christ just as his footballing life was about to take off.

He had a stellar football career and a stellar second career at the BBC as a football pundit on Match of the Day. But Peacock then turned his back on it to go into church ministry.

He now works as a pastor in Canada, writes books, and occasionally watches the videos of the season when he scored the winner both home and away for Chelsea against Manchester United. But Peacock still says his biggest thrill is Jesus:

When your identity is in Christ, when your supreme joy is in him, football can come and go but he’s always there, so there’s a greater thrill, a deeper joy, that transcends difficulties and trials.

That freedom means he’s playing a better second half.

And the other player? The great black icon, Cyrille Regis, who put up with the monkey chants and bananas from the 1970s and 1980s terraces to reign supreme, with a killer strike and a mega-watt smile.

He too had everything in that first half of the game. Or so he thought. One day his close friend, fellow black footballing trailblazer, Laurie Cunningham, flipped his car after a party in Spain and was killed. And Cyrille got to thinking, “What if that were me?”

There were so many questions in my heart. One of the biggest things that sank into my thinking was, here was me and Laurie; fame, money, influence, power, cars, adulation, and Laurie took nothing with him. And I’m thinking, so what’s life all about?

At that point, just approaching half time, Cyrille Regis decided to put his trust in Jesus, and to carve out a second half which would be better than the first.

He became one of the sport’s best ambassadors, a man who nurtured a whole generation of black footballers; who loved his family and his church community; and took every opportunity to serve people who needed help.

But here’s what he had in common with George Best. He died at 59. Two years ago. Suddenly. Without warning, in his sleep after attending Sunday evening church. The streets were lined with thousands as his coffin went past. Grown footballers wept their gratitude.

And by trusting Jesus, what did Cyrille Regis take with him that Laurie Cunningham didn’t? Everything. Maradona may have delighted in the hand of God. But Cyrille now delights in the face of God.

How is the second half going for you? Are you playing it better or worse than the first? Will you emulate Maradona and Best? Or Peacock and Regis?