A guest post by James Garth a Fellow of ISCAST with an active interest in the science/faith interface.

From time to time someone asks me what my favorite Bible verse is, and I have a ready-made answer: Acts 26:25. Most people haven’t heard of it, as it’s much less well known than John 3:16. It goes like this:

“I am not insane, most excellent Festus,” Paul replied. “What I am saying is true and reasonable.”

This usually gets a laugh, and it’s certainly an amusing phrase at first glance. But after the laughter dies down, I like to point out that the verse is, in fact, an authentic one, and I’m serious about it being my favorite.

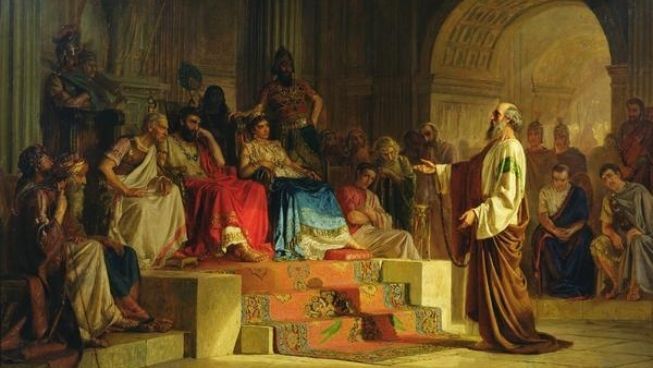

It appears in the context of St. Paul's trial before the Roman governor Porcius Festus, to whom Paul has been brought to answer trumped-up charges of sedition and instigation of public unrest. These charges were laid by local Roman authorities in response to a speech Paul gave to a crowd in Jerusalem, which nearly instigated a riot – a not uncommon occurrence in the politically charged atmosphere of first-century Palestine.

In an entertaining exchange, Paul attempts to persuade Festus' superior, King Agrippa, of his authenticity by employing reason and the testimony of his personal experience. Paul gives a detailed description of the vision that he experienced on the road to Damascus and engages with Jewish scriptures and traditions in order to build a case for the truth of Christianity, a fledgling movement which has sprung into the world amidst claims of the alleged resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. At the height of the debate, in a fit of frustration, Festus vents: “Paul, your great learning is driving you mad!” to which Paul earnestly replies: “I am not insane, most excellent Festus. What I am saying is fair and reasonable.”

What interests me about this verse is how Paul has no qualms whatsoever in putting certain evidence on the table to support his claim that God raised Jesus from the dead and that this Jesus appeared to him personally. He clearly thinks that he has good warrant for his beliefs. I think Paul would want to strongly challenge certain twenty-first century critics of Christianity, who have said “faith is belief in the absence of evidence, even in the teeth of evidence”. And he wouldn’t have much time for that old Mark Twain adage, “faith is believing what you know ain’t so.”

No, such definitions would be rejected by Paul. Indeed, the approach Paul adopts in Acts 26:25 is part of a remarkably consistent pattern that he demonstrates as his engagements with the Roman authorities unfold in the book of Acts. If you haven’t had the pleasure of reading this account, I especially commend the section from chapter 20 to 26 to you; it can be read in well under half an hour and is a ripping story.

Alister McGrath provides an excellent commentary on the ‘Acts apologetic speeches” in his book “Mere Apologetics: How to help seekers & skeptics find faith”. McGrath notes “the New Testament itself develops a variety of apologetic arguments and styles of engagement, clearly intended to facilitate connection with each specific envisaged audience”. He identifies three specific audiences in particular:

Jews – devout monotheists familiar with the scriptures

Greeks – agnostics, seekers and philosophers

Romans – pagans, polytheists and citizens of Empire

Of these three audiences, it is Paul’s address to the Greeks at the Areopagus (or “Mars Hill”) in Acts 17 that resonates most closely with me, living in a culture choked by different worldviews at war. We’ve become so saturated with information that we suffer information fatigue and become wary of commitment, and yet we remain “uncomfortably haunted by the memory of religion”, as Rowan Williams puts it. To the Greeks – and to us too – Paul tailors his approach by arguing that the “unknown god” can be known more fully through Christ.

The take-home message from these speeches and from Acts 26:25 is this: it is not sufficient for the critic to claim that “there is no evidence” for Christianity. No, Paul is going out of his way to actively try and provide evidence. That’s his whole intention: to engage and persuade.

A fairer and intellectually respectable response would be to say, as Graham Oppy has, that “there are no good arguments for the existence of God that ought to persuade those who have reasonable views to change their minds” (my paraphrase). That’s a perfectly acceptable position for a non-believer to take.

But notice that the conversation has changed. We have moved from a blunt “there is no evidence” to “there is no evidence presented by Christian apologists that I find compelling.” And it’s by reading the Bible itself that we find support for this shift.

It’s a significant shift, and I think it moves the discussion in a much more fruitful direction. We’ve gone from “playing the man” – attacking a person for believing arbitrarily and not producing any evidence – to “playing the ball” – debating the nature of evidence itself, and what constitutes good evidence.

That’s the game we need to be playing. And that’s why Acts 26:25 is my favorite Bible verse.

Image: Nikolai Bodarevsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References:

McGrath, A., Mere Apologetics: How to help seekers & skeptics find faith, Baker Books, 2012, 197 pages.

Oppy, G., Arguing about Gods, Cambridge University Press, 2006. 449 pages.