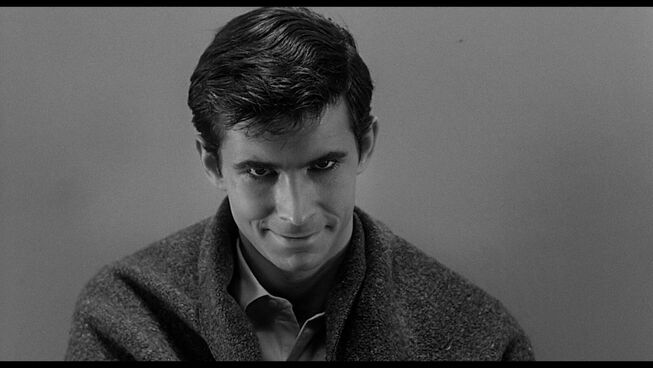

“Over the bar on which hangs the shower curtain the audience watches Marion as she washes herself. The noise of the shower drowns out any sound as the bathroom door slowly opens. The shadow of a woman falls across the shower curtain and the white brightness of the bathroom is almost blinding. Suddenly, a hand reaches up, grasps the shower curtain, and rips it aside. A look of pure horror erupts on her face. A hand comes into the shot. The hand holds an enormous bread knife. The slashing. An impression of a knife slashing, as if tearing at the very screen, ripping the film. Over it the brief gulps of screaming. And then silence. And then the dreadful thump as Marion’s body falls in the tub.” - Shower Scene, Psycho Script – December 1959

Adapted from the 1959 novel by Robert Bloch, Psycho follows an Arizona real estate secretary, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), who skips town after stealing $40,000 in cash from her employer. Marion is conflicted by the desire to pay off her divorced lover’s debts, so they can marry and mounting guilt over her crime. Exhausted, she later pulls off to the side of the highway and falls asleep in the car. The next morning Marion is awakened by a suspicious police officer who follows her to California Charlie’s used car lot. The all-knowing eye of the state trooper adds to Marion’s growing sense of condemnation when she hastily and awkwardly trades in her Arizona vehicle for one with California licence plates. Later that night it begins to storm, and the windshield wipers struggle to keep up with the downpour. The water could symbolise the washing of Marion’s guilty conscience as she begins to have second thoughts. Marion comes upon a shabby, backroad lodge called the Bates Motel where she meets the young dissociative motel owner, Norman Bates (played by a brilliant Anthony Perkins). Norman lives with his withdrawn yet a domineering mother in a gothic mansion overlooking the motel. The audience learns that Mother disapproves of Norman consorting with young and attractive women. Mother doesn’t approve of a lot of Norman’s decisions. In her motel room, as she prepares to turn in for the night, Marion decides she will return the money the following day. However, she will never get the chance.

Alfred Hitchcock is one of only a handful of directors whose entire body of work has influenced generations of filmmakers. Ironically, Psycho is perhaps Hitchcock’s most famous film and arguably, his career-defining achievement. The legendary director later admitted that his approach to making Psycho was little more than “tongue-in-cheek.” He envisioned the production as a “big joke” that manipulated the viewer’s imagination into thinking they saw something when they did not. This is evident in the film’s unusual structure, including the iconic shower scene. Hitchcock breaks several moviemaking rules in this scene while assaulting the viewer’s visual and auditory senses. He subjects his leading actress, Janet Leigh, to a violent murder halfway through the film. It took seven days to shoot 45 seconds of film. There are an astonishing 78 separate camera setups and 52 disorienting cuts (pardon the pun). Initially, Hitch intended for the shower scene to be filmed without music until legendary composer and frequent collaborator, Bernard Hermann, sampled the now infamous “Murder” track. Who can forget the piercing staccato of violin strings as the camera convulses from one bewildering image to the next? Hitchcock was so impressed with the film’s score that he nearly doubled Hermann’s salary. It took less than 60 seconds of film to impact the viewer’s imagination so indelibly that Hitchcock did not need to use violence to punctuate the rest of the narrative. The scene causes a “trauma” that colours how he/she experiences the rest of the film.

Upon its release in June 1960, a peculiar thing happened outside the DeMille and Baronet theatres in New York City. Anxious moviegoers stood in long lines waiting for the next screening of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Every couple of hours, the next group of patrons was ushered into a packed theatre to watch the 109-minute film from start to finish. On their way past the concessions area, viewers were greeted by a cardboard image of the eccentric auteur pointing at his wristwatch and a sign that read:

WE WON’T ALLOW YOU to cheat yourself! You must see PSYCHO from beginning to end to enjoy it fully. Therefore, do not expect to be admitted into the theatre after the start of each performance of the picture. We say no one – and we mean no one – not even the manager’s brother, the President of the United States, or the Queen of England (God bless her)! – Alfred Hitchcock.

Hitchcock’s “no late admissions” strategy for Psycho was almost unprecedented in 1960; consequently, managers feared the policy would hurt ticket sales. It is difficult for modern moviegoers to imagine a time when double features played on a continuous loop with people freely entering and exiting the theatre at any point during the showing. In fact, before 1960, movie theatres rarely listed showtimes in newspapers, and couples who planned on “going to the movies” simply walked into the darkened theatre at a random point in the narrative. Sit there long enough and eventually, one person would lean over and mutter a common catchphrase of a bygone era: “This is where we came in.” Today it is unthinkable to arrive intentionally late to a showtime and it would be considered unnecessary and even offensive for a director to use his/her trailer to demand that exhibitors shut out late patrons. Alfred Hitchcock’s brilliant marketing trick was much more than a clever publicity stunt. He invited moviegoers to participate in the discovery of suspenseful storytelling and to wait for the inevitable payoff at the end.

Reel Marriage

Lights, Camera... Movies and Marriage!

Marriage is one of life’s greatest blessings, yet it faces countless challenges in today’s world. How can we strengthen our commitment and help others see its value? The Bible offers wisdom, but what if movies could serve as a bridge to deeper conversations about love, faith, and commitment?

Reel Marriage explores how film and Scripture can illuminate the beauty of marriage, providing fresh insights into God’s design for love and relationships. From classic romances to modern dramas, movies capture couples' struggles and triumphs, mirroring biblical truths in powerful ways.

Faith and film unite. Are you ready to see marriage in a whole new light?

If you order your copy today you will also receive a complementary handbook that is only available with the purchase of the book (Print or ebook)

Despite the critical acclaim and box office success of another Hitchcock classic, North by Northwest, the legendary director couldn’t get a major studio to fund Psycho. Studio executives were convinced that tastes had changed. They assumed audiences preferred big Technicolor productions with principal photography done on location rather than on constructed sets. Compared to North by Northwest, Psycho’s production was small and confined to the studio backlot. Most importantly, however, the script broke too many rules, and Hollywood simply wasn’t prepared to go against conventional wisdom. Determined to realise a vision that his allies at Paramount could not see, Hitch turned to his television company, Shamley Productions. The famed director hired the same production crew that filmed his weekly television series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. To save money, Hitchcock filmed in black-and-white and used studio sets and backlots. Chocolate syrup mixed with water was famously used to imitate blood, and a sound mix of knives slicing through various melons and cuts of beef was used to mimic the impaling of flesh. Hitch agreed to waive his usual fee in exchange for 60% of ticket sales if Paramount agreed to distribute the film. Incredibly, Hitch completed production for just over $800,000, and the film went on to gross $50 million. To date, Psycho is the highest grossing black-and-white film of all time.

If you are looking for a good slasher flick to watch this Halloween watch where it all started. Psycho touches on themes of guilt, covering sin, and family on a deeper level.