1.5 out of 5 Stars

Writer and director Paul Schrader has atonement on his mind in his new film, The Card Counter. He is best known for his works as the director for First Reformed and the writer of Taxi Driver and the infamous The Last Temptation of Christ. With this outing, he directs a slow burn of a film with fabulous themes, yet manages to overcook every ingredient to an incredibly dull effect.

William Tell (Oscar Isaac) is an ex-military interrogator turned card-counter who gambles for small pots in casinos up and down the East Coast of the United States. Bill is content with his dull, monotonous life of playing cards day in day out, week after week. He is obsessed with the action that cards provide. Yet, as with many of Schrader’s characters, his obsession is a cover for deep trauma. Beneath the veneer of a card shark is a deeply haunted man, tortured by the demons of his past decisions. Every night, knowingly or unknowingly, Bill wrestles with deep, theological issues regarding atonement as he logs his every thought and memory in his journal. Some of his ponderings wonder how he can heal the guilt he carries in his soul. Mainly if the former interrogator can ever truly atone for the sins of the past.

During a chance encounter at a casino, Bill meets a young man named Cirk (Tye Sheridan), who shares a mutual enemy from past his military life. While Cirk is bent on vengeance, Bill sees his chance at atonement. Can Bill pay for his past sins by helping this young man make better choices with his life?

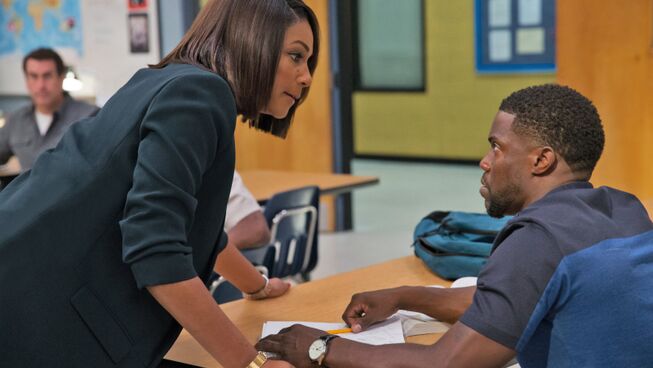

With his long-standing reputation in Hollywood, Schrader can pull together a deep bench of talented actors. Unfortunately, many of their performances are wasted in this tediously dull, neo-noir. Oscar Isaac does carry the film with his star quality and charisma, making it difficult to take your eyes off him. While Tiffany Haddish is likeable, Tye Sheridan is forgettable, and Willem Defoe barely makes a cameo.

Schrader begins the film with a clear sense of focus, establishing the world of card-counting the game of Black Jack. The celebrated writer/director immerses his audience in the world of competitive gambling. Yet it takes nearly half the film to discover what is really going on just beneath the surface of Isaac’s simmering Bill Tell. Though act one is an intriguing on-ramp into this world, by the end, it feels like Schrader left Chekhov’s gun* in the other room. Very little established in the opening act pays off in conclusion. Exciting themes and ideas are introduced only to be immediately abandoned, making the viewer scrambling to figure out which pieces are essential to the overall narrative. By the end, it all feels like the director has put together pieces of a puzzle gathered from different sets. The thematic through-line of atonement does track, but the journey to the destination is so boring, it is hard to care by the time you get to the destination.

The Card Counter gives us insight into the damaged psyche of post-Iraq soldiers. Like many of the character’s he has written before, Schrader holds nothing back. He lets us see the damage done to these men who were trained to do horrible things in the name of National Security.

Reel Dialogue: Can anyone truly receive atonement?

Underneath the dull slog of the screenplay, the film does ask a relatable and vital question. How do we atone or pay for the sins of our past? This is a poignant question anyone can relate to because everyone has regrets and guilt. Similar to Schrader’s thematic through-line is the thematic thread of the entire Bible which addresses this issue of atonement.

God directly answers how our sins can be paid for and to whom and by whom they are to be paid. If you would like to learn more about what God has to say, the Gospel of John is a great place to start as he shows how all of scripture, over thousands of years, has been about this one theme, atonement.

*Chekhov's gun is a dramatic principle that suggests that details within a story or play will contribute to the overall narrative. This encourages writers to not make false promises in their narrative by including extemporaneous details that will not ultimately pay off by the last act, chapter, or conclusion. Find out more details at Screencraft